Freestyle Kick: The Complete Guide

In This Article

Even though it’s not responsible for a large amount of propulsion, you need to focus on your flutter kick because it holds your stroke together.

In this section of our freestyle guide, we show you how to perform flutter kick properly and common mistakes you need to watch out for, in addition to providing drills, sets, and dryland exercises that’ll keep your flutter kick in tip-top shape.

This is the detailed page on freestyle kicking. You can find the other three parts of the stroke broken down in detail below.

Freestyle kick is the glue that holds your stroke together. It performs many small functions that may seem inconsequential at first, yet their absence can be devastating. Freestyle kick, also known as flutter kick, is an alternating leg kick performed with relatively straight legs. It’s typically performed at a relatively high rate over a small range of motion.

There are two components to flutter kick. There is a downbeat in which your leg moves from the surface of the water to a depth of about 12 inches. The downbeat is powered by your quadriceps, which creates knee extension, and by your hip flexors, which bring your thigh down.

The reverse of that motion is called the upbeat. The upbeat is powered by your hamstrings and glutes, which serve to lift your leg back up to the surface of the water.

Your legs work in opposition in flutter kick. When one leg kicks down, your other leg kicks up. Although the downbeat is responsible for most of the positive effects of kicking, the upbeat is equally important because it sets up the next downbeat.

Your flutter kick performs several important functions.

It works to maintain your body position in the water by keeping your hips up. By keeping your hips up, you’ll face less drag as you move through the water, reducing how much energy you expend.

It assists in rotating your body side to side, making your rotation smoother and more effective. Your rotation is key to facilitating effective arm recoveries and arm pulls. The kick can help make the side-to-side transition effortless.

It can positively contribute to propulsion, aiding your arms. Although your arms create most of the propulsion, your legs can contribute significantly.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

The Multiple Roles of Kick

Flutter kick plays three important roles that contribute to speed.

- The first is intuitive and obvious: Kicking directly creates propulsion. A fast, powerful kick can create a lot of speed, especially over shorter distances. Because a powerful kick is fatiguing, you should only use it over shorter distances. Your kick is most effective when you perform it at a high rate of speed, rather than with a large amplitude.

- The second role is less obvious yet no less important: Your kick serves to counterbalance any arm, breathing, or body motions that move your body out of alignment. For instance, the beginning of your pull causes your hips to sink, and the harder you pull, the more your hips sink. A strong kick counteracts this sinking effect.

- If you’ve ever swum with a band around your ankles, you immediately notice how much more difficult it is to keep your body in line. That’s because your kick can no longer serve this important function. As a result, you have a lot more body movement with each stroke. Fortunately, these counterbalancing actions tend to happen naturally, much like how we naturally react upon stumbling on land by using our arms and legs to maintain balance. Because it’s nearly impossible to remove every action that puts us off balance, your kick is incredibly important in helping you move forward.

- Finally, your kick helps to create the side-to-side rolling rhythm in your stroke. A strong downward kick will shift the same-side hip up in an equal and opposite reaction. If your right leg kicks down, your right hip will move up and your left hip will move down, shifting your body from the right to the left. Although your arms also facilitate your body rotation, this extra action by your kick can smooth out the rotational process. This is why all effective kicks have a two-beat pattern at their base.

The Two Phases of Kicking

There are two primary phases of flutter kick: your legs move up and your legs move down. The down-kick, when your leg moves from a high position in the water to a low position in the water, serves a propulsive role. In contrast, the up-kick, when your leg moves from a lower position up to a higher position in the water, serves a preparatory role, readying your leg for the next down-kick. (You do receive some propulsion during the up-kick, though much less than you receive during the down-kick.)

From a timing perspective, your legs move in opposition. As one leg performs the up-kick, the other leg performs the down-kick. The timing of your legs is intertwined. Each leg finishes its respective phase at the same time and reverses course at the same time.

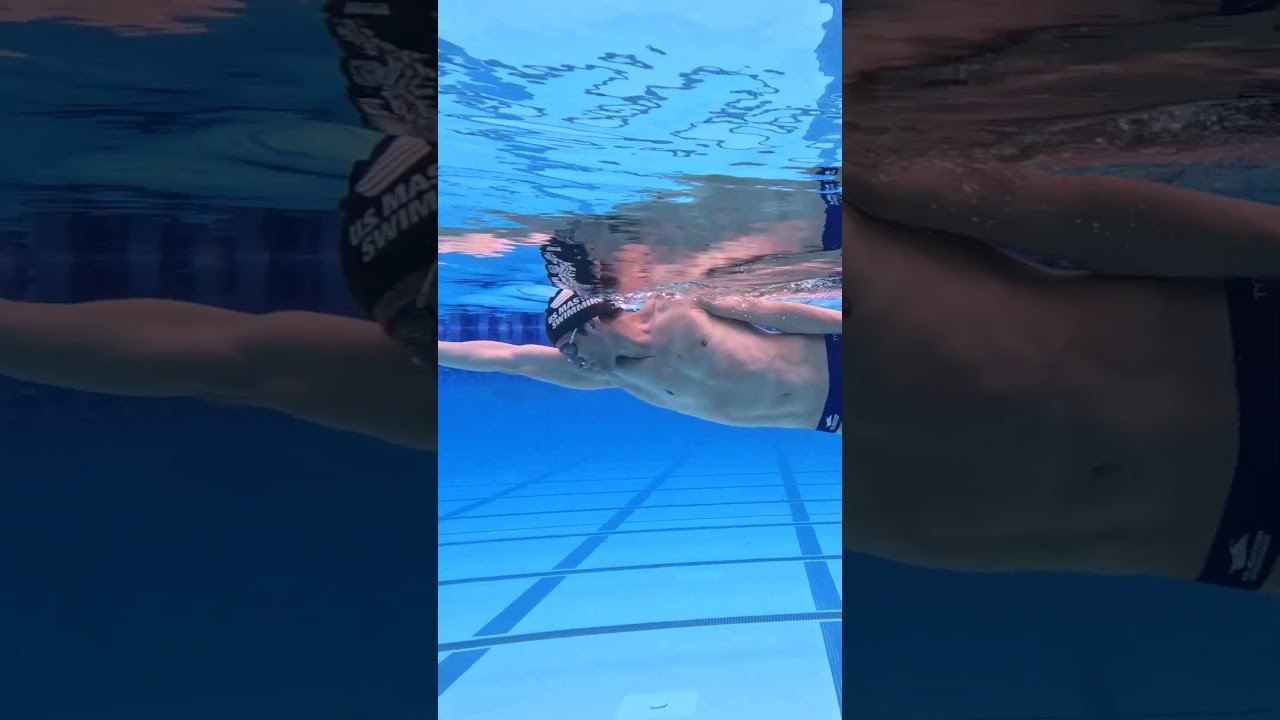

Your down-kick begins at your hip, your knee moves second, and your ankle moves third. As your leg moves through the kick, you generate more speed. Your knee moves faster than your hip and your foot moves faster than your knee. Think of a whip creating a wave of acceleration.

With your down-kick, there’s a significant amount of knee bend (about 120 degrees). But remember: Your kick starts from your hip and not from your knee. If your kick happens at your knee first, you’ll lose the whipping action.

During your up-kick, your kick also begins at your hip. However, in contrast to your down-kick, you should have little to no bend in your knee during the up-kick. For many, effectively executing your up-kick will feel like you’re kicking with straight legs. This is an important aspect of your kick because it effectively prepares your legs for an effective whipping action during your down-kick. Although some propulsion can be created with your up-kick, the primary role of your up-kick is to prepare for the subsequent down-kick.

Common Kicking Mistakes

Flutter kicking is unlike kicking during any activity on land. Although all kicking actions originate at your hips and travel down your leg to your foot, the kicking action in the water is much smaller and tighter. This is particularly true about your knee’s range of motion. In contrast, kicking a ball feels like a predominantly knee-driven action, but kicking from your knees while swimming is problematic.

- The most common mistake swimmers make while kicking is initiating their kick with their knee and excessively bending their knee. Doing so eliminates the whip action of your kick, which is essential for creating propulsion. Not only does this reduce propulsion, but it also tends to drop your knee lower in the water, increasing the amount of drag created and the energy used to swim. Using a kick that feels extremely straight tends to correct this problem.

- The second most common kicking mistake is bringing your feet up and out of the water during your kick. Although this may feel effective because it’s hard and it may look effective because it creates a lot of noise and splashing, a foot that’s not in the water cannot create propulsion. This mistake often arises from the belief that it’s necessary to kick as hard as possible rather than as effectively as possible. Keep your kick right at the surface of the water.

- A final mistake that swimmers make is to exaggerate their kick with the belief that it should be as strong and as powerful as possible with little regard to timing. Your kick should be coordinated within the rhythm of your stroke. Simply kicking as hard as possible prevents you from appropriately timing your kick.

Types of Kick (Six-Beat, Four-Beat, Two-Beat)

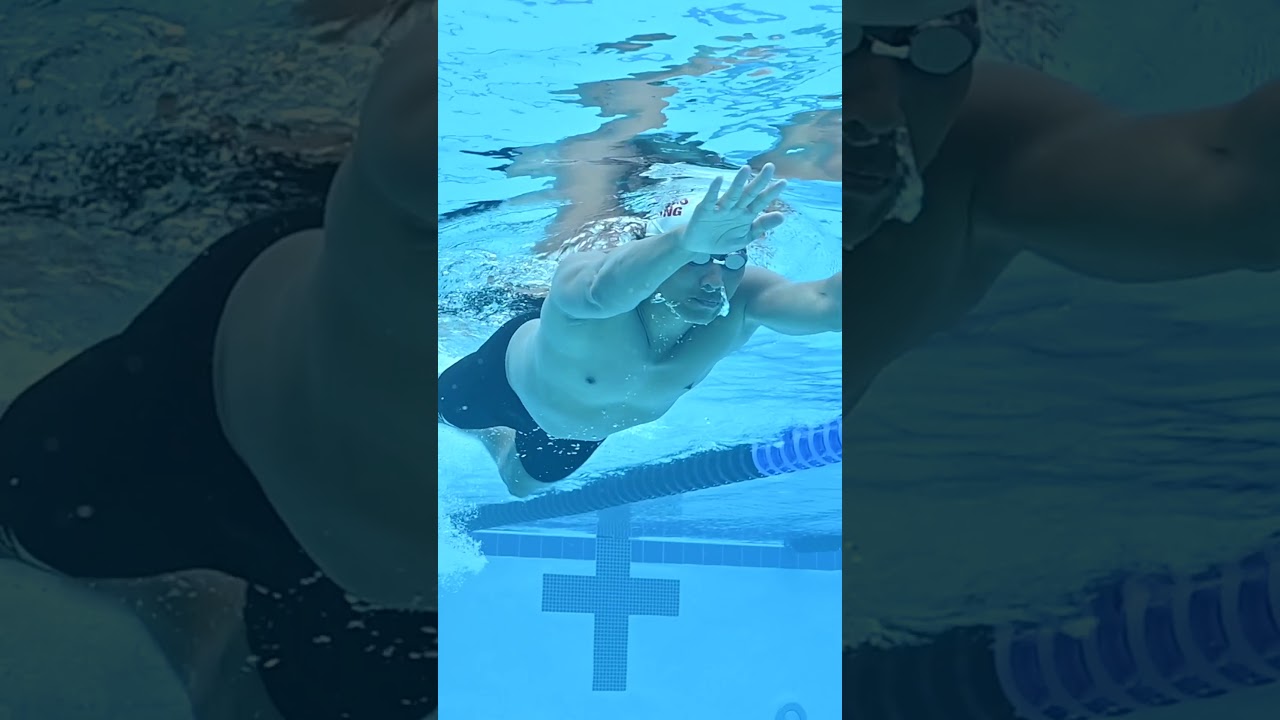

Effective kicking is about effective timing as much as it’s about creating propulsion. The timing of all effective kicking rhythms is based around a two-beat pattern. The two-beat kicking pattern coincides with the side-to-side rotation of your body. When your left arm enters the water, your left hip and shoulder move down to rotate your body from your right side to your left side. At the same time, your right leg kicks down to rotate your right side up, further facilitating the shift to the left side of your body. The same thing happens on the other side.

In this way, the two-beat kicking pattern assists the rotation of your body, making it faster and easier. Although you’ll still rotate if you aren’t kicking, you’ll rotate much more effectively with your kick. To feel this in action, swim with a pull buoy and be very disciplined about not kicking. Better yet, add a band. You’ll find the rotation to be much more robotic without your kick.

A six-beat kicking pattern has the same basic timing but with the addition of two smaller kicks per leg during each stroke cycle. The main two-beat pattern still exists in combination with the other kicks. The six-beat pattern has the advantage of increasing the amount of propulsion created, as well as counteracting the sinking force of your hips that results from the arm pull. Despite these extra kicks, the two primary kicks still occur at the same time as they would in a two-beat kick to facilitate the rotational rhythm of your stroke.

The four-beat kick is a hybrid of the six-beat and the two-beat timing. One side of your leg is using a six-beat pattern and one side is using a two-beat pattern. This can emerge as a natural pattern for some individuals, and it’s not necessarily problematic, provided the primary two-beat is still occurring within it.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

The Size of Your Kick

Determining the appropriate size of your kick is all about trade-offs. Kicking will create both propulsion and drag. Propulsion speeds you up and drag slows you down. It’s like the gas and the brake. If there’s more gas than brake, you’ll speed up. The larger the difference between the two, the more you’ll speed up. In contrast, if the brake is stronger than the gas, you’ll slow down, and the bigger the difference, the faster you’ll slow down.

The shape and range of motion of your legs and feet limit how effective your kick becomes when you use kicks of various amplitudes (how far up and down your feet go). As your kick gets bigger, it gets harder to keep your foot oriented backward. Your foot must be oriented backward so that water can be moved backward. Thus, a progressively larger kick creates progressively less additional propulsion. Although a moderate-sized kick can create a lot more propulsion than a small one, a large kick doesn’t create much more propulsion than a moderate-sized kick.

Every time your foot leaves the shadow of your body, it creates drag, just as when you stick your arm out of the window of a moving car. With a large kick, your foot will move far deeper in the water, moving farther outside the shadow of your body. As a result, a bigger and bigger kick will create more and more drag. A bigger kick doesn’t necessarily create more propulsion.

The bigger your kick, the more energy you need. As the size of your kick increases, you’re creating progressively more propulsion and progressively more drag. Because the increases in drag are a lot more than the increases in propulsion, the result is less speed.

Using Your Kick Strategically

Kicking is expensive. It takes a lot of energy to produce speed with your legs, and a big kick takes a lot more energy than a smaller kick.

In short sprints of 50 yards or meters or less, you’ll want to fully employ your kick to create as much speed as possible. It’s all about maximizing speed with little concern for energy conservation. In longer races such as the 1500 meters or 1650 yards, you’ll want to be conservative with your kicking until you get to the final sprint to the finish. With every race in between, there’s a lot more discretion as to how to best use your kick.

When racing over intermediate distances, if a strong kick really helps your speed and your legs are well conditioned, it makes sense to incorporate your kick. In contrast, if having a strong kick doesn’t improve your speed much, or if your legs aren’t conditioned to sustain your kicking, a more conservative approach is warranted. Determining your strategy over a given race distance comes with practice and experience. By using various levels of kicking during training sessions and competitions, you’ll begin to develop an intuitive sense of how much to kick. When you’re aware of the importance of moderating your kick, this process happens much faster.

In the beginning of races beyond 50 yards or meters, it’s useful to go light on your kick to conserve energy. Rather than intentionally slowing down the speed of your legs, reduce the effort of your kick. Regardless of the racing distance, it can be effective to use your kick as a strategy for shifting gears. If you want to make a move in a race, or respond to someone else’s move, increasing your kick is a great way to do so. Simply work your kick more to increase your speed. However, this strategy is only possible if you were appropriately conservative in the beginning of a race.

- All of the articles were written by Andrew Sheaff

Kick Drills

Streamline Kicking on Your Back

Many swimmers overemphasize their down-kick at the expense of their up-kick, predominantly by kicking at their knee.

Flutter kicking on your back can help expose this weakness. This drill can help develop the muscles of the back of your leg (your hamstrings) and reinforce a more balanced kicking action. Your goal should be to ensure that your knees remain at or beneath the surface of the water while kicking, rather than breaking through the surface.

Vertical Kick

By kicking vertically instead of horizontally, you’ll be able to focus on kicking with straight legs rather than bent knees. This forces you to kick from your hips rather than your knee. It’s much easier to perceive the ability to kick with straighter legs while vertical.

Kicking on Your Side

Kicking on your side builds upon the skills you develop while doing vertical kick. Although it’s more challenging to kick in both directions while kicking on your side compared to when you’re kicking vertically, the benefit is that you’re now moving forward through the water, just as when you’re swimming freestyle. Furthermore, it’s easier to kick in both directions when you’re on your side than with a kickboard, making this a great drill to transition between vertical kicking to kicking on your stomach. This drill also helps you work on your body positioning and alignment, which you’ll need to work on to maintain the rigid posture that helps you move forward effectively.

Wall Kick

Much like you can learn to hold water with your hands, you can learn to hold water with your feet. This is more difficult to do, however, because of the shape of your feet.

One strategy for improving your ability to feel what’s happening with your feet is to kick against resistance. The wall is the perfect, no-cost way to create resistance. Because there’s no movement involved, the resistance is even higher. Wall kick helps you quickly learn which strategies create the most resistance against your feet, and thus create the most propulsion.

Snorkel Kicking

Swimmers often do kick sets with their head held high, such as while using a kickboard. Although there’s some benefit to this, it doesn’t help you learn to kick while in the same body position used while swimming properly.

Effective kicking with a snorkel requires a tighter, more compact kick that reduces drag. Kicking with a snorkel encourages you to kick from your hips rather than your knees to minimize the amount of drag created.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

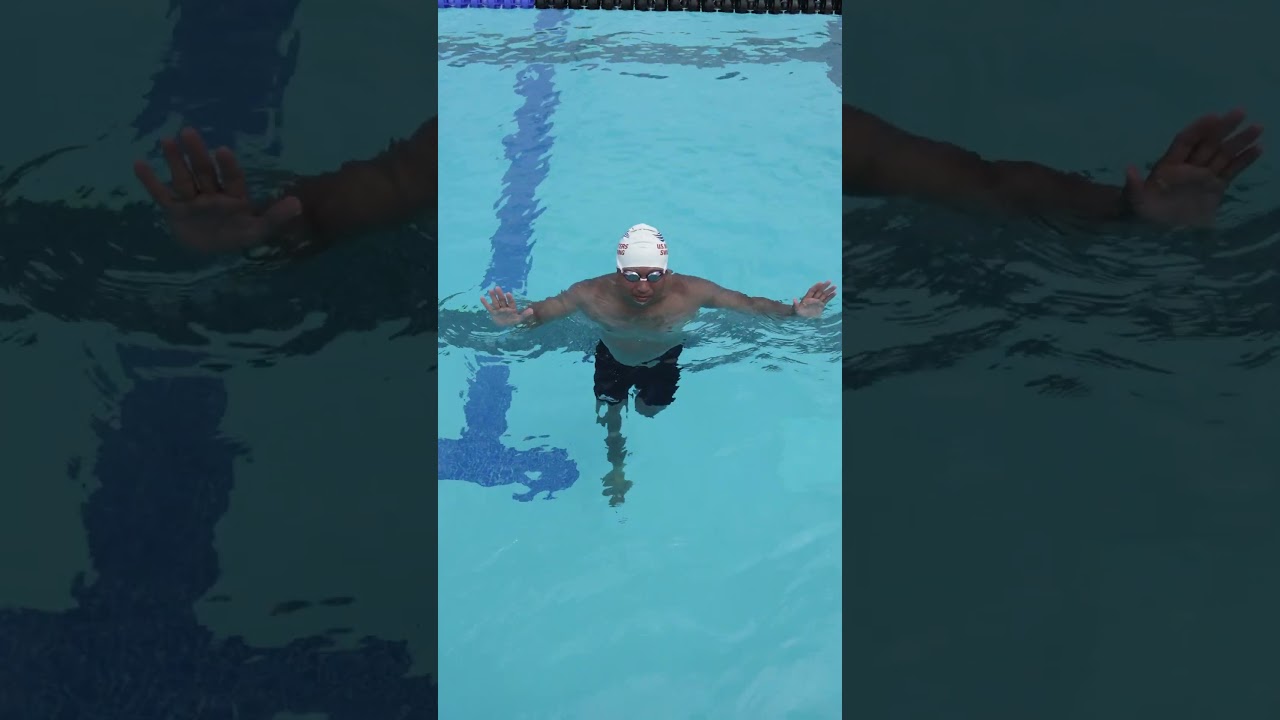

Surf Kicking

One of the major roles of your kick is to counteract the sinking force of your hips created by your arms. By kicking with your hands outstretched, your head up, and no kickboard, your legs are naturally going to sink.

To keep your hips up, you’re forced to kick strongly. Because you’re also working to move forward through the water, this drill forces you to perform both roles of your kick at the same time with a high degree of expertise. You need to keep your hips up and maintain your speed at the same time.

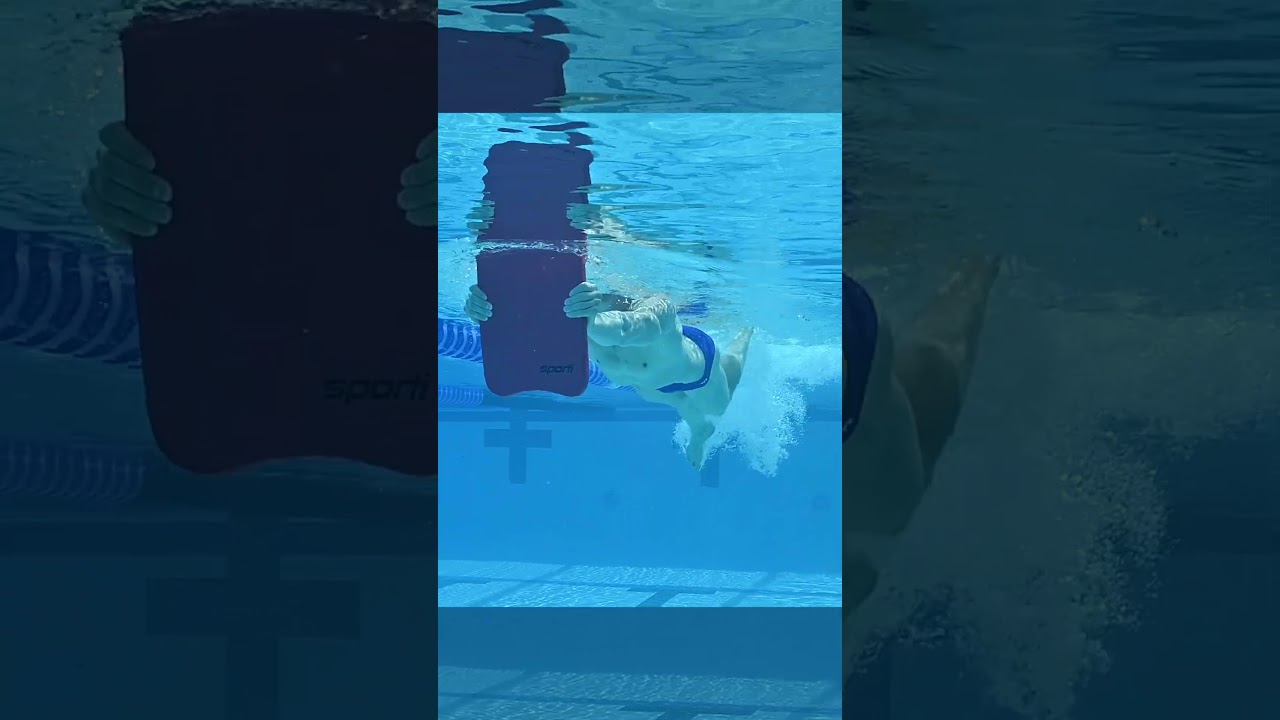

Tombstone Drill

Tombstone drill, in which you hold the flat surface of a kickboard out in front of you, is like wall kick in that the added resistance can help you learn to create propulsion with your feet. Although there’s not quite as much resistance because you’re moving forward, the forward movement makes this exercise slightly more comparable to unresisted flutter kicking. It functions as a bridge between wall kicking and regular kicking. Like wall kicking, it’s an option that can be used by anyone with widely available equipment. It’s also a perfect activity for racing against teammates or training partners.

Resisted Kicking (DragSox, Parachute, Board Shorts, etc.)

Because you don’t get as much resistance against your legs as you do your arms, determining how to apply force in the water can be difficult. Resisted kicking can help you feel more pressure on your feet. This allows you to learn how to kick properly.

A particular benefit of a product such as DragSox is that it reinforces your kick’s whipping action that starts at your hip. If you kick predominantly from your knee with DragSox, your progress will be almost nonexistent.

Over-Kicking

Over-kicking helps with the process of learning to integrate an improved kick into your stroke. Over-kicking is what it sounds like: an exaggerated kick coupled with an exaggerated, slow arm recovery. The goal is to swim freestyle while creating speed from your legs rather than your arms. This is a great way to train your kick in a very specific manner. Note that this isn’t an effective way to swim. It is a training activity used to condition your legs while swimming freestyle.

Stroke-Count Kicking

Stroke-count kicking is a more precise version of over-kicking. Choose a stroke count that’s significantly lower than normal, such as four to six fewer strokes. For example, if you normally take 15 strokes, you’ll take nine to 11.

To get across the pool, you’ll have to increase your kick. If you’re also expected to go fast while stroke-count kicking, you’ll have to create speed with your kick. When performing this exercise, your goal is to transition from stroke to stroke as smoothly and as rhythmically as possible.

- All of the drills were written by Andrew Sheaff

Kick Sets

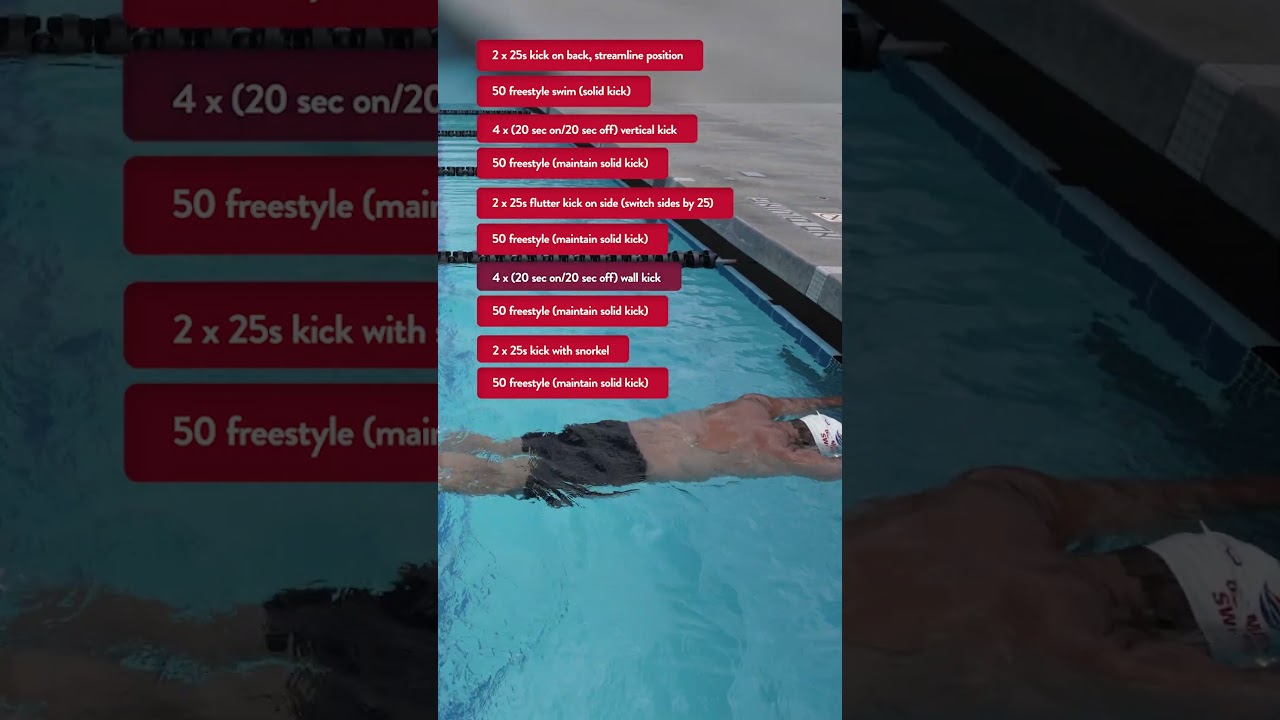

Set 1

(2–3 times through)

Take 15–20 seconds rest between repetitions

- 2 x 25s kick on your back in streamlined position

- 50 freestyle swim (solid kick)

- 4 x (20 seconds on/20 seconds off) vertical kick

- 50 freestyle (maintain solid kick)

- 2 x 25s flutter kick on your side (switch sides by 25)

- 50 freestyle (maintain solid kick)

- 4 x (20 seconds on/20 seconds off) wall kick

- 50 freestyle (maintain solid kick)

- 2 x 25s kick with a snorkel

- 50 freestyle (maintain solid kick)

Purpose and Focus Points

The purpose of this set is to introduce you to various modes of kicking. Kicking in a variety of situations helps you get broad exposure to the different aspects of effective kicking.

Kicking on your back in streamlined position helps you feel your kick behind your body. Vertical kicking helps you learn to kick in both directions, leading from your hip. Wall kick helps you feel pressure on your feet. Kicking with a snorkel helps you learn to use a tight kick.

All these kicking styles feel different, and when you’re able to feel new ways of kicking, you’re going to be able to create change. Between each kicking style, you’ll perform some freestyle to help you learn to integrate those changes into your swimming.

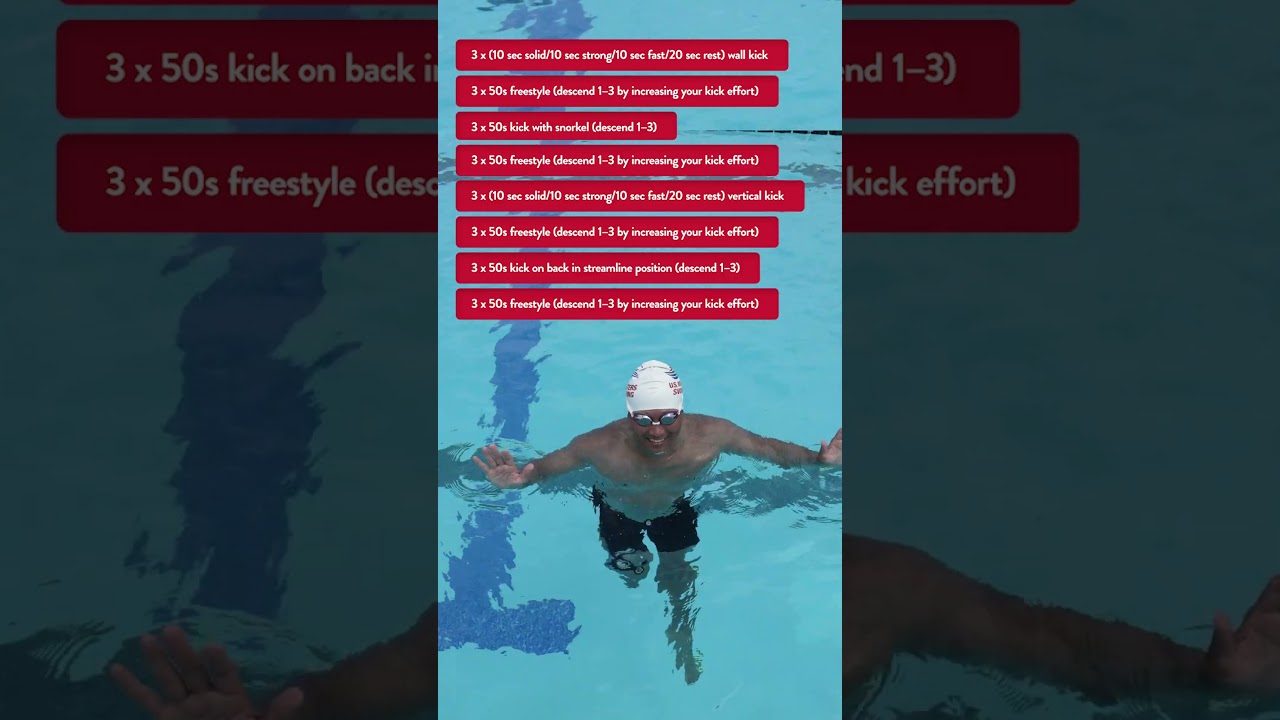

Set 2

(2 times through)

Take 15–20 seconds rest between repetitions

- 3 x (10 seconds solid/10 seconds strong/10 seconds fast/20 seconds rest) wall kick

- 3 x 50s freestyle (descend 1–3 by increasing your kick effort)

- 3 x 50s kick with snorkel (descend 1–3)

- 3 x 50s freestyle (descend 1–3 by increasing your kick effort)

- 3 x (10 seconds solid/10 seconds strong/10 seconds fast/20 seconds rest) vertical kick

- 3 x 50s freestyle (descend 1–3 by increasing your kick effort)

- 3 x 50s kick on your back in streamlined position (descend 1–3)

- 3 x 50s freestyle (descend 1–3 by increasing your kick effort)

Purpose and Focus Points

The purpose of this set is to learn how to create speed with your kick. You’re going to do so in several different kicking contexts, as well as when swimming regular freestyle. When you’re forced to create speed, you’re forced to kick more effectively. When you’re kicking more effectively using different styles of kicking, you’re going to develop a broader kicking skill set.

In learning how to integrate all these changes into your freestyle, you’ll find it’s less about how fast you end up going and more about changing speeds. The goal is to figure out how to create speed in each situation and do so consistently and predictably. Once you can do that, you’ve learned how to modify your kick for speed.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

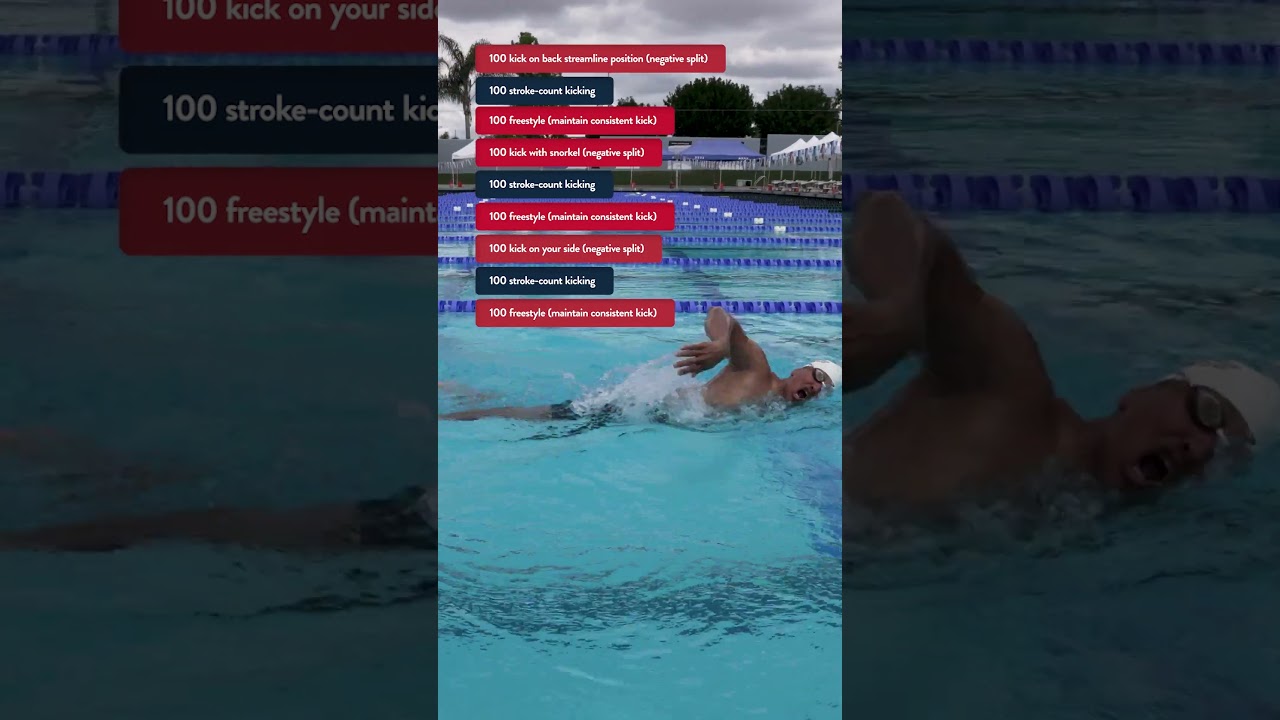

Set 3

(1–2 times through)

Take 20–30 seconds rest between repetitions

For stroke-count kicking: Take 4–6 fewer strokes than normal per 25 and drive your kick to create speed. Aim to maintain a fluid rhythm as much as possible.

- 100 kick on back in streamlined position (negative split)

- 100 stroke-count kicking

- 100 freestyle (maintain consistent kick)

- 100 kick with snorkel (negative split)

- 100 stroke-count kicking

- 100 freestyle (maintain consistent kick)

- 100 kick on your side (negative split)

- 100 stroke-count kicking

- 100 freestyle (maintain consistent kick)

Purpose and Focus Points

This set builds upon the previous sets and adds an endurance component. These distances are longer than the previous ones, and there’s an emphasis on more continuous swimming. The goal here is to sustain your kicking effort.

For the kicking 100s, focus on creating speed during the second 50. On the remaining 100s, focus on a consistent kick while swimming.

During the stroke-count kicking, the purpose is to learn how to use your legs while swimming. By aggressively restricting your stroke count, you’ll have to compensate with your legs. As much as possible, aim to make this rhythm as fluid as possible. Although this can be a challenge at first, the result is a kick well integrated into your stroke.

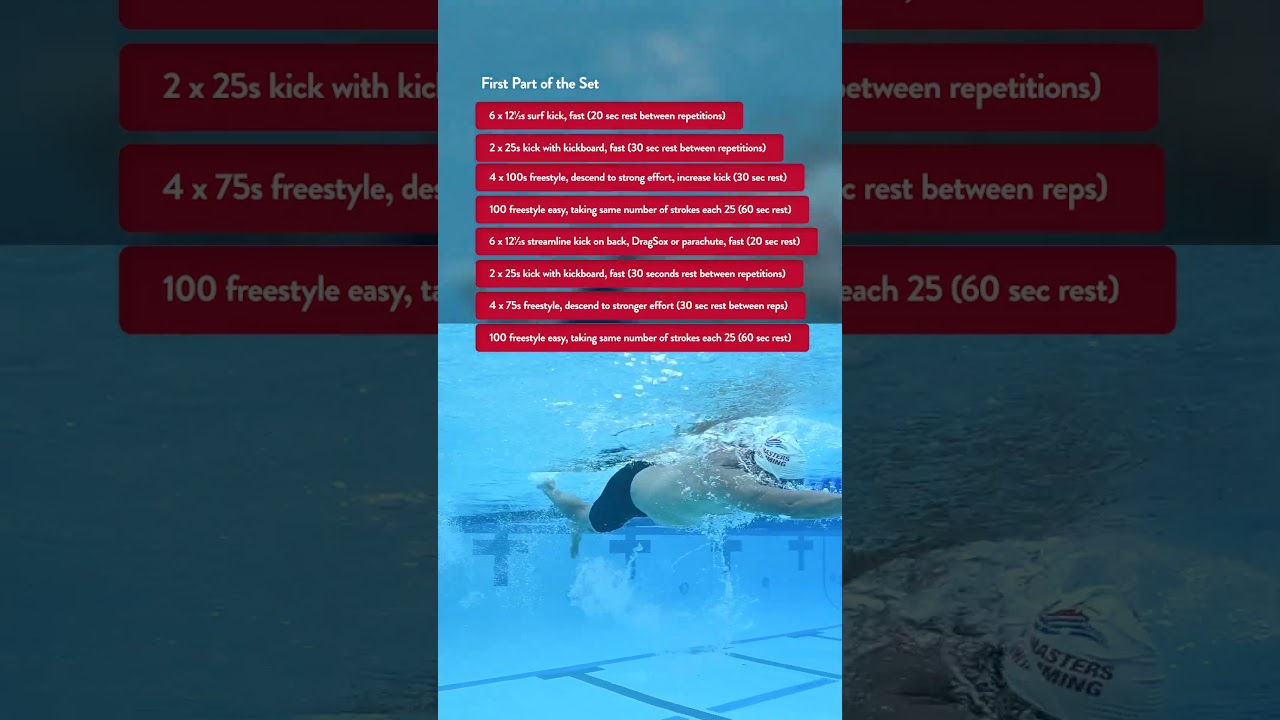

Set 4

- 6 x 12.5s surf kick, fast (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 2 x 25s kick with kickboard, fast (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 4 x 100s freestyle, descend to strong effort by increasing your kick effort (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 100 freestyle, as easy as possible while taking the same number of strokes each 25 (60 seconds rest)

- 6 x 12.5s streamline kick on back with DragSox or parachute, fast (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 2 x 25s kick on kickboard, fast (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 4 x 75s freestyle, descend to stronger effort by increasing the kick (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 100 freestyle as easy as possible while taking the same number of strokes each 25 (60 seconds rest)

- 6 x 12.5s tombstone drill, fast (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 2 x 25s kick with kickboard, fast (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 4 x 50s freestyle, descend to strongest effort by increasing your kick effort (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 100 cruise (maintain a steady pace you can easily hold), same stroke count (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 6 x 12.5s kick with kickboard, fast with DragSox (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 2 x 25s kick on kickboard, fast (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 4 x 25s freestyle, descend to fast effort by increasing your kick effort (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 100 freestyle, as easy as possible while taking the same number of strokes each 25 (60 seconds rest)

Purpose and Focus Points

This set is all about creating high speeds with your kick. The resistance work is designed to help you learn how to move water with your feet. Because of the increased resistance, you’ll be better able to feel the water on your feet and push it backward with the whip-like movement of your kick. You’ll then work on kicking fast without the resistance. Finally, you’ll focus on swimming progressively faster by incorporating a more powerful kick.

Throughout the set, you’re learning how to use your legs several ways, all with a focus on speed. Focusing on moving fast with your legs while swimming will help you accomplish the goal of a kick that creates speed.

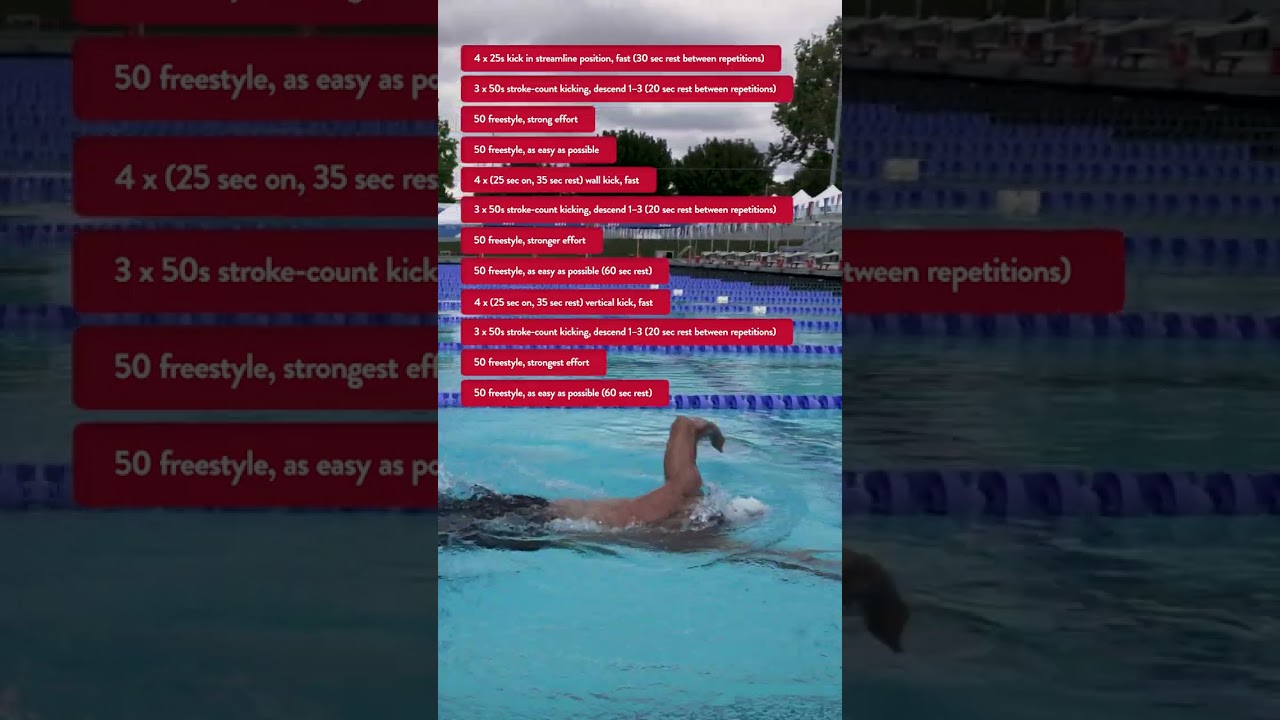

Set 5

For stroke-count kicking: Take 4–6 fewer strokes than normal per 25 and really drive your kick to create speed. Aim to maintain a fluid rhythm as much as possible.

- 4 x 25s kick in streamlined position on your back, fast (30 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 3 x 50s stroke-count kicking, descend 1–3 (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 50 freestyle, strong effort

- 50 freestyle, as easy as possible (60 seconds rest)

- 4 x (25 seconds on, 35 seconds rest) wall kick, fast

- 3 x 50s stroke-count kicking, descend 1–3 (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 50 freestyle, stronger effort

- 50 freestyle, as easy as possible (60 seconds rest)

- 4 x (25 seconds on, 35 seconds rest) vertical kick, fast

- 3 x 50s stroke-count kicking, descend 1–3 (20 seconds rest between repetitions)

- 50 freestyle, strongest effort

- 50 freestyle, as easy as possible (60 seconds rest)

Purpose and Focus Points

This set continues the theme of creating speed with your legs. You’ll perform different kicking exercises at high speed. The goal is to learn how to kick in both directions at high speed and maintain pressure on the water with your feet.

The next goal is to learn how to create swimming speed with your legs. With a limited stroke count, you’ll have to create speed with your legs. Because you need to go faster each repetition, you’ll need to create more speed with your legs each 50.

Finally, without the constraint of a stroke count, you’re free to let it rip while still using your legs on the last 50. The goal is to get better with each 50 each round.

- All of the sets were written by Andrew Sheaff

Dryland Exercises

Ankle Sit

Flexible ankles are key to an effective kick. A flexible ankle allows for more of the top of your feet to face backward during each kick. When that happens, you’ll be able to push more water backward and, therefore, yourself forward.

The ankle sit is a simple way to mobilize your ankle in a safe and controlled manner. It’s important to patiently increase the duration and the intensity of the stretch to avoid injury.

To perform this exercise, use a mat or other padded surface. You can be barefoot or wearing shoes while doing this exercise. Simply sit on your heels so that the top of your foot is pressed straight into the ground, with your hips sitting on top of your heels. Depending on your comfort with the exercise, you can begin with lightly sitting on your heels rather than placing all your weight through your foot. Placing a chair next to you so that you can support your weight can be useful for this purpose.

Ankle ABCs

This exercise is like the ankle sit except that it’s an active movement instead of a passive one. The purpose is to move your ankle through a full range of motion using many different patterns. This ensures that full mobility of your ankle is established.

It’s valuable to actively train ankle mobility because it ensures that you possess full control of the range of motion. Do this exercise regularly to improve your range of motion over time.

To perform this exercise, lie on your back and lift one leg off the ground. With that leg, begin to “write” the ABCs, one letter at a time, making the letters as big as possible. Go through the entire alphabet with one leg, then switch to the other. This can be done with lower case letters, upper-case letters, or both. Alternatively, this exercise can be performed in any position where your leg is relaxed and your ankle can be freely rotated.

Goblet Squat

The goblet squat is a simple strength exercise accessible to everyone. It strengthens your hips and the front of your legs (your quadriceps), key muscles in generating a powerful kick. It also trains your torso, which is important because a straight and tall posture is required to prevent the weight from being dropped.

Beyond the benefits to your kick, the goblet squat can improve your starts and turns. This exercise can be loaded as heavily or as lightly as desired, provided you can hold the weight.

To perform this exercise, grasp a dumbbell of appropriate weight. Hold the dumbbell with both hands under one head of the dumbbell, holding it like a goblet. The weight should be resting on your chest. While maintaining an upright position, squat down under control in between your knees, then return to a standing position. Keep the dumbbell in the goblet position throughout.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Back Extension

Your down-kick is often much stronger than your up-kick while doing flutter kick on your stomach. As a result, the muscles on the back of your legs, including your hamstrings, are often underdeveloped and undertrained. This only makes the imbalance worse.

Performing exercises such as the back extension, which targets your hamstrings and glutes, addresses this issue. By strengthening these muscles, your kick can become more balanced.

To perform this exercise, use a back extension device like the one in the above video demonstrating this exercise. Adjust your foot placement so that your hips are slightly in front of the pad. Secure your legs into the back of your foot placement. Lower your upper body under control until it’s vertical. Then squeeze the muscles on the back side of your body to lift your upper body until it is parallel to the ground. Pause briefly. Return to the bottom position under control.

Split Squat

Some people have one leg that’s stronger than the other, so training each leg individually in the split squat ensures both legs are trained equally.

The split squat trains similar muscles as the goblet squat does, but it also trains muscles that ensure stability in your hips, such as the adductors and gluteus muscles. This is because this is a single-leg exercise. Although these muscles can contribute to kicking speed, they also ensure that your legs remain healthy.

To perform this exercise, hold two dumbbells of appropriate weight, or you can do split squats with just your bodyweight. From a standing position, take a large step forward, keeping your back leg in place. From this position, lower your body straight down until your back knee is just off the ground. Press into the ground and raise your body straight up. Aim to keep your body straight without leaning or bending over. Your feet should not move throughout.

Physioball Leg Curl

As with back extensions, this exercise targets your hamstrings and glutes, the strong muscles on the back of your leg. In contrast to back extensions, this exercise trains your hamstrings by bending your knee rather than extending your hip. This ensures that you’re training these underdeveloped muscles.

This exercise also requires you to apply force with patience and stability, which is relevant to all swimming movements. This exercise should be performed slowly at first, then more rapidly if you’re maintaining control.

To perform this exercise, lie on your back with your knees bent, heels resting on a stability ball. Your legs should be bent. Lift your hips off the ground so that your weight is on your shoulders. From that position, roll the ball away. Once your legs are straight, dig your heels into the ball and pull them toward your hips. This should push your hips toward the ceiling, returning you to the initial position.

Prone Flutter Kicking

Kicking from your knee is one of the most common mistakes with flutter kicking. Prone flutter kicking reinforces the proper straight-leg technique of flutter kicking while training your abdominals and hip flexors. By developing the muscles responsible for executing a straighter kick, you’ll develop the fitness to sustain this action as your legs begin to fatigue in the water.

Initially, this exercise can be performed patiently over a large range of motion. As your skill and fitness improves, it can be performed faster over shorter ranges of motion.

To perform this exercise, lie flat on the ground on your stomach. Your legs should be straight, and your arms should by your sides. Squeeze the muscles of your back and hips and lift one leg off the ground. Hold briefly, then return to the ground under control. Repeat with your other leg. Rather than moving for speed with this exercise, aim to move with control over a large range of motion. This can be done one leg at a time, or by having your legs move in opposition, with one moving up as the other moves down.

Supine Flutter Kicking

Kicking from your knee is one of the most common mistakes with flutter kicking. This exercise reinforces the proper straight-leg technique of your kick while training your glutes and hamstrings.

This is a more specific version of the exercises previously performed to strengthen the back of your legs. These muscles are often underdeveloped, especially in the range of motion used with this exercise. Lift each leg with control and hold it at the top. Once you’ve developed consistent strength and control, you can increase your speed.

To perform this exercise, lie flat on the ground on your back. Your legs should be straight. Lift both legs off the ground while ensuring your back stays pressed into the ground. Keep your arms out at your sides. With straight legs, make a small flutter kicking action. Your range of motion should be small. It’s key that your back stays flat on the ground. That may require that your legs be lifted higher into the air. Do so if necessary, aiming to lower your legs over time.

Prone Physioball Kicking

This exercise builds upon the previous ones, encouraging the proper straight-leg technique of your kick at a high speed. Your goal is to move your feet as fast as possible.

This exercise should be performed fast. Some swimmers may be able to kick with straight legs at slow speeds but struggle at fast speeds. The prone position reinforces the strength of your abdominals and hip flexors.

To perform this exercise, assume a plank position with your feet on a physioball. Have a partner hold the physioball. Begin to kick as fast as possible. Move your feet as fast as possible while using a small kick, aiming to keep a straight line from your shoulders to your toes. Keep your upper body and torso as still as possible.

Supine Physioball Kicking

As with the previous exercise, supine physioball kicking should be performed fast.

To perform this exercise, lie on your back on the ground with your feet on a physioball. Lift your hips off the ground. Have a partner hold the physioball. Begin to kick as fast as possible. Move your feet as fast as possible while using a small kick, aiming to keep a straight line from your shoulders to your toes. Keep your upper body and torso as still as possible.

- All of the dryland exercises written by Bo Hickey

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

This is the detailed page on freestyle kicking. You can find the other three parts of the stroke broken down in detail below.

SIGN UP FOR UPDATES FROM USMS